The text about Cornel Dober is a foreword to the brochure ‘Korn, das in die Erde fällt. Sie gaben ihr Leben für andere’ (‘The grain that falls into the earth. They gave their lives for others’), which will be presented in the upcoming SMB ‘Exchange’.

We present here an English translation of this text published on June 3 on the website www.imbethlehem.ch.

The missionary life is not marked by glory, but by the folly and powerlessness of the Cross, which assures the believer that God acts mightily.

When Cornel Dober recorded this reflection in 1956, he was barely aware that the powerlessness of the Cross would descend upon him in the form of a violent death twelve years later.

Cornel Dober was born on January 31, 1927, in Küssnacht am Rigi. He was the third child in a family of five. His grandfather had sold land to Pierre Barral, on which, in 1921, the Gymnasium Bethléem and the Bethlehem Mission Society were founded.

This is how Cornel Dober was able to pursue his secondary education at the neighboring high school, where he obtained his Matura in 1947. At the end of his schooling, he decided to commit to missionary service.

After the probationary year at the Schöneck missionary seminary, he joined the Bethlehem Mission Society in 1948. Christianus Caminada, Bishop of Chur, ordained him a priest on Palm Sunday, April 11, 1954, in Stans. Six months later, he was sent on a mission to the Diocese of Gweru, Zimbabwe.

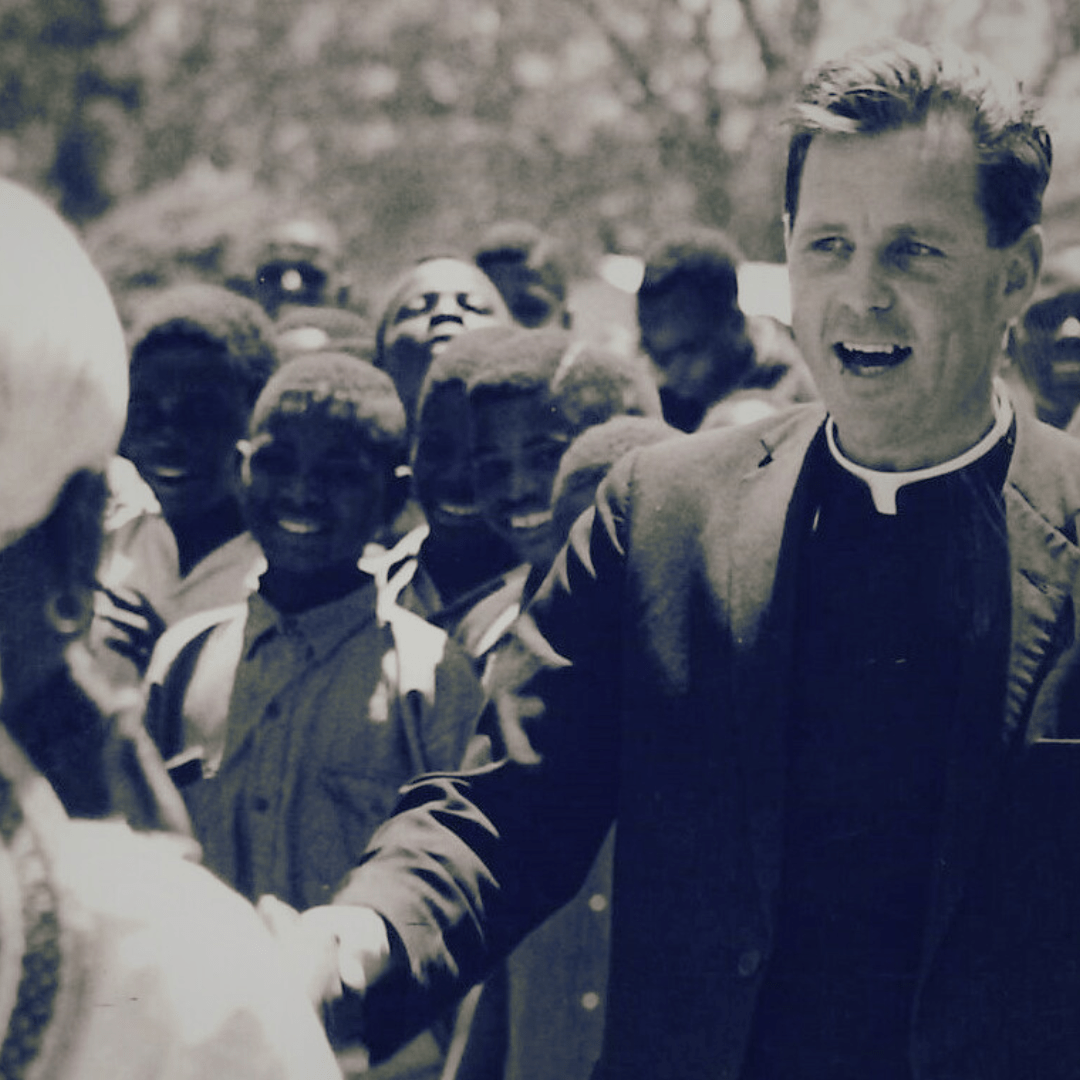

Due to his commitment to the poor, many people nicknamed him the “Martin de Porres of Gweru.” His deep knowledge of customs and living conditions, his pastoral zeal, and his love for Africans won their hearts.

Five years later, the bishop appointed him superior of the main mission in Driefontein. Thanks to his diplomacy, humor, and special talent for mediation, he was able to create genuine cohesion among the various groups in Driefontein: the confreres, the indigenous sisters, the teachers and apprentices in the workshops, the workers on the mission farm, the staff and the tuberculosis patients in the sanatorium, the students of the mission school, and the new missionaries at the regional house.

His efficiency and zeal led the bishop to appoint him to the episcopal council, and his confreres elected him to the regional council. From 1966, he was responsible for the Chilimanzi deanery, and in 1967, he represented the region as a delegate to the Chapter. His work was also appreciated in various other committees. As a member of the diocesan and national Liturgical Commission, he contributed to liturgical inculturation and renewal. He was particularly concerned with a suitable funeral liturgy.

However, this dedicated and appreciated work, which had raised so many hopes, was abruptly interrupted. On the afternoon of January 14, 1969, a young African man came to the mission asking for the last rites to be administered to a dying relative. Cornel Dober was ready to provide this service. The young man sat on the back of the motorcycle and directed him along the way. About five kilometers from the mission, the passenger stabbed the missionary in the carotid artery, took his watch and the keychain granting access to the mission station, and then disappeared into the bush. The motive for the crime was apparently the mission’s money.

Cornel Dober tried to stop the bleeding with his handkerchief and return to the mission. But his strength quickly waned. He lay down and bled to death, still carrying the Eucharist with him. A boy passing by the spot informed a woman in a nearby shop. She alerted the mission. But help arrived too late; the mission doctor could only confirm the death.

The funeral at the Driefontein Mission cemetery was a testimony to the local people’s esteem for their missionary, whom they soon began to venerate as a saint.

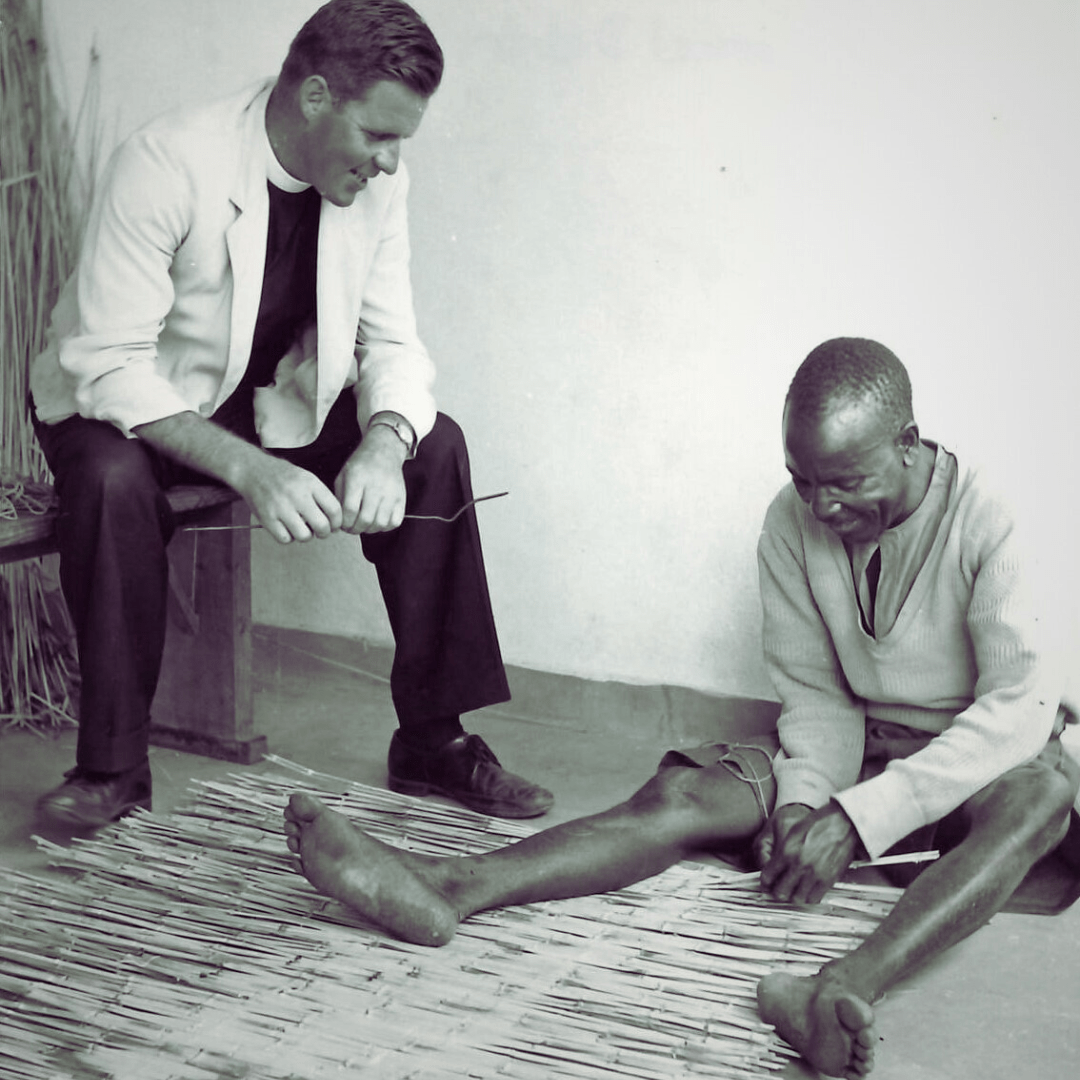

Cornel Dober, pastor and superior, in discussion with a local craftsman

A fellow missionary tried to understand what this death triggered: why must such a thing happen? But his death could not have better crowned his life. Cornel Dober did not calculate; he gave and helped without counting the cost. In this country, a missionary is called to help every hour. Some grow weary and build a shell around their hearts. This was not the case with Cornel Dober. The only thing one could reproach him for was being too good. In his madness, he gave everything, including his young blood. And in this madness, Christ was literally with him on his chest as he lay dying in the bush: two inseparable friends.

It was in this communion with Christ that Cornel Dober wrote twelve years before his death, inspired by the Apostle Paul:

‘The powerlessness of the apostle and the missionary is a participation in the distress and anguish of the Lord of the Gospel himself. The powerlessness of the apostle is a communion of death with Christ, for apostleship means sharing the destiny of Christ. Thus, in the life of the missionary, in his endurance and his victory over powerlessness, the life of Jesus becomes visible, as the work of the sovereign power of God.’

Brother Albert Plangger notes that the violent death of Cornel Dober brought the missionaries together under the Cross like no other event in the thirty-year history of missionary presence in Zimbabwe—because the mission leads sooner or later to the Passion.

According to biblical categories, the servant of God must suffer… But now that one of us has been stabbed to death, we are all deeply affected by such a brutal and senseless act. Faith must give us the strength to go beyond it and see in it a meaningful mystery, closely linked to the passion and death of the Redeemer Christ.

The Passion is not only the result but also, in a way, the culmination of every mission. Only in this way does the mission become fruitful, and the cross will remain until the fulfillment…

Mission also means self-giving, whether peacefully or violently, but it is above all an offering.

Josef Werlen SMB / Ernstpeter Heiniger SMB

Comments are closed.